Reinforcement Learning Conference: an exploration step in reviewing

RLC decisions came out recently; congratulations to all the accepted papers and thank you to everyone who submitted a paper. The aim of this post is to shed light on the new processes that we hope will result in a better research publishing and conference experience. Rather than choosing a particular target acceptance right, we chose to focus on technical rigor and checking “does this paper’s evidence match its claims''. In addition, inspired by TMLR, senior area chairs were empowered to further evaluate if RLC represented an appropriate and non-trivial audience for the work (and thus judge novelty and positioning of the work as well). Finally, we aspired to uphold high scholarly standards, meaning clarity, writing, and polish were held to a high standard. Judgements on significance, focus on state-of-the-art claims and more generally “taste making” were discouraged.

How did this new approach work out? We are excited to report that we wound up with a 40% acceptance rate and 115 accepted papers, which is right in line with early versions of other ML conferences. Having said that, it’s a new process so we wanted to take this time to go over some of its interesting aspects, clear up some misconceptions, and discuss future improvements we are considering.

The Process

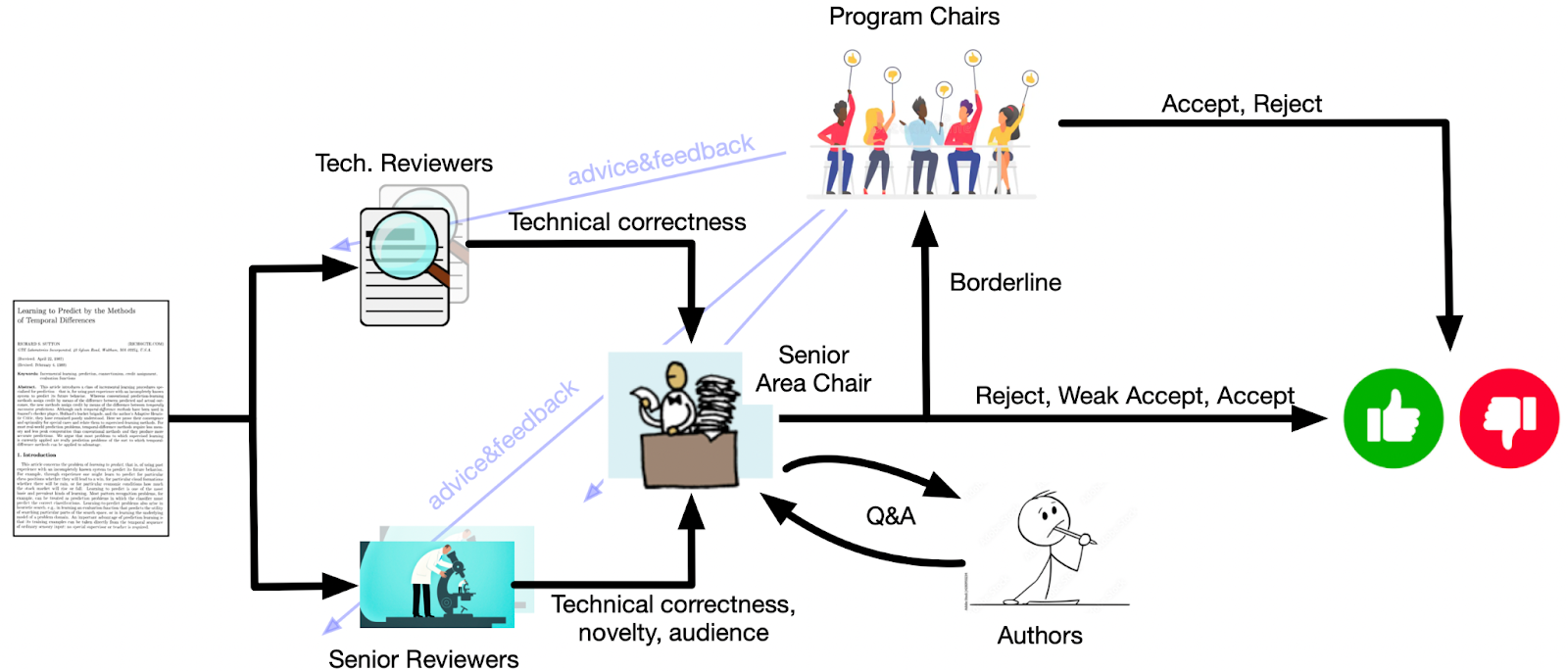

Our approach to improving reviewing was to reduce workload for reviewers, but ask for increased effort and quality from every reviewer per paper. In particular, we asked slightly less of our technical reviewers (who were typically more junior researchers, but not always), by having them only assess technical correctness, and relied on our senior reviewers to handle both technical correctness as well as more subtle factors like relevance to the field. The combination of these two reviews was then passed to a senior area chair (SAC) who synthesized the two, read and evaluated the paper (effectively a third reviewer), and then made a final call. These SACs we handpicked—senior folks with years of experience post PhD and known to be both generous to new ideas and have excellent judgment.

The program chairs were active at all stages of the process: giving comments and suggestions to improve both technical and senior reviews, discussing and troubleshooting issues with the SACs, and helping make final decisions about borderline papers. [In our system, if an SAC rated a paper as borderline they were communicating to the program chairs they needed help making the final call on the paper. All such cases were discussed by the PC.] Each PC member was assigned as a “buddy” to several SACs. The PC buddy provided a direct communication channel for questions, concerns and discussions about each paper, for each SAC. The full review process is summarized in the diagram above. Overall, each paper was read by four people and the decision was based on information from all four people.

The final decision process worked as follows. The SAC made the final decision based on (1) reading the paper, (2) the two reviews, (3) discussion with the reviewers and the PC, and (4) (optional) direct Q&A with the authors. If the decision was reject, weak accept, or accept that decision was mapped to reject, accept, or accept respectively. If the SAC marked the paper as borderline, then the PC made the final decision. This is the process visualized in the figure above.

Note that at the scale we’re operating at, we were able to handpick many of the reviewers, but still, many needed course correction. The program chairs, SACs, and many senior reviewers went to great lengths to identify and improve low-quality technical reviews. First, the technical reviewers were reminded of the reviewer guidelines and asked to improve their reviews. If the review was not updated satisfactorily, then a new technical reviewer was added. In several cases, the PC noted parts of technical reviews that were judged to be violating the spirit of the review process. We followed a similar process for attracting and improving senior reviews, including adding another senior reviewer in some cases. By large, this group was well known to the PC and organizers and the quality of these reviews was quite good. Like any conference, there were uncommunicative senior reviewers—and SACs—but nothing worth noting. Someone from the PC read every technical and senior review submitted to RLC.

This new process was an experiment—no system is perfect—but we believe this system is better for RLC than the standard approach. Our primary goals were to reduce workload, increase review quality, and focus on correctness and quality rather than taste. This was not easy and required a new process. Furthermore, this was a big change for our reviewers, who are accustomed to the typical review style that focuses primarily on the perception of significance and impact. It will take multiple iterations to fine-tune this system, but comments from the community suggest we are on the right path. We are excited about the papers that are accepted to RLC and looking forward to meeting all the authors. We will also continue to iterate and improve the system based on the results of this first experiment and feedback from the community.

What went well

We were happy with several aspects of this new review process. The feedback we received from folks in the community that our focus, on claims matching evidence and correctness, was seen as a breath of fresh air and a good way forward. Most importantly, we tried something very new and we now have data and comments to improve the process going forward.

The engagement and feedback provided to technical reviewers early on in the process by PCs, SACs, and SRs was effective. Many technical reviewers actually engaged and updated their reviews significantly. In cases where there was a lack of engagement, we assigned new reviewers from our pool of emergency reviewers, ensuring the review process continued smoothly. As mentioned, this required significant engagement from PCs throughout the process, which we will need to rethink to allow RLC to grow.

The detailed guidelines for TRs, SRs, and SACs were helpful to many. These guidelines provided instructions and expectations, helping to maintain consistency and quality across all reviews. Naturally, these documents can be sharpened and consolidated, but they provided a guidance for both reviewers and authors. Sharing these documents with authors before the submission deadline provided transparency and perhaps helped align submissions with the conference’s goals.

The design of the review process was based on the principle of subtraction and appears to have had the desired effect. Typically, when things are not working well, people add new things: more reviewers, more tasks for reviewers and ACs, etc. This creates much more work, but often does not improve things. Subtraction, stripping things back to the barebones, can be a more effective alternative. This was the goal of introducing technical reviews, removing traditional author response, and reducing the number of reviewers overall. We believe the workload for technical reviewers and senior reviewers was much less than usual. For SACs, who typically must read reviews, discussions, author response, and long dialogs in OpenReview for up to five reviews per-paper, the workload was similar but now the SAC’s time was put into reading the papers and writing more detailed meta reviews. Overall, we think workload was reduced and decision making accuracy was at least maintained and likely improved.

Finally, the introduction of PC buddies for SACs proved to be quite helpful. This system made it clear who the point of contact was for each SAC, facilitating better communication and support throughout the review process. We received constructive comments from several SACs on how to do this even better next year!

Looking forwards

There are a number of changes that we are contemplating in the next edition of RLC.

Continuing to improve reviewer guidelines

Many technical reviewers, instructed only to check for technical correctness, submitted almost one-line reviews of the form “this is correct.” In many cases, the paper under review was excellent and this one-liner corresponded to an extremely thorough review! However, a paper author would not be able to tell if this review was thorough or not. In future years, we will likely have more detailed TR review instructions that make their work more visible.

Reviewing software and libraries

Software and libraries are a key part of RL in practice but require a slightly different review process. We’re now starting the process of figuring out what a good, thorough review cycle would look like for software contributions.

Continuing to refine and grow our pool of reviewers

Initially, there were many low-quality technical reviews. We cannot be sure why. Some may have found the instructions confusing; some might not have dedicated enough time to the process; many clearly did not read the instructions and template matched to reviews they typically write. Others we know either lacked the ability to check correctness or refused to do so. Many reviewers who previously won reviewing rewards from major conferences produced some of the lowest quality reviews and never responded to comments or suggestions from the PC. Whatever the reason, we were quite surprised at the quality of some of the technical reviews; improving them required significant effort from the PC—and that will not scale as RLC grows.

We have to have an honest conversation with our community about mechanism design (rewarding good reviews) and training people on how to review papers. If folks do not take reviewing seriously and with an attitude of generosity towards the work, then the whole process breaks down. We can do better; we must do better!

Review town hall

We will likely host a town hall to discuss the process and address questions raised. We will be soliciting questions in advance of the conference so that we can address and discuss the most common ones. We are also very excited to get people from the community more involved and look forward to discussing ideas to improve this process for the future.